Today, the Ancient Near East is in vogue. Da’esh has popularized concern about Antiquities by publishing propagandist videos about their destruction of monuments and artifacts in both Iraq and Syria. Many who keep up with the art market are also familiar with the influx of artifacts from that region finding their way into galleries and pawn shops across the Western world. Analysts predict that the sale of Antiquities accounts for the second largest source of revenue for Da’esh next to oil, though this claim is disputable given the difficulties in collecting evidence of the origins of undocumented artifacts. Antique trafficking also has a long track-record in the Middle East, long before Da’esh turned to heritage as a way to fund their activities in the region. Thanks to the warnings published by the FBI, propagated by the media machine, and the propaganda Da’esh creates itself, members of Western society are more apt to identify the motifs and works of the past. However, the legacy of the Assyrians has influenced artistic productions in the West since the discovery of Nimrud and Nineveh in the mid-1800s. Earlier this month my colleague Tiffany published an article about cultural appropriation in Art Deco movements highlighting the role of Egyptian and Islamic motifs in architecture and decorative arts. Similarly, I would like to discuss how Pre-Raphaelites, Romantic artists and Symbolists alike kept the memory of the Assyrians alive in their works through comparable means of appropriation.

In academia, the term Orientalism is tossed around regularly in courses of study. Orientalism describes Western attitudes toward the Eastern other during the height of imperialism and colonialism. The phenomenon has resulted in dangerous dichotomies of savage/civilized, primitive/developed, and ignorant/religious to outline a few. These classifications justified European intervention into Africa and the Middle East, and paved the way for Austen Henry Layard’s excavation of the Neo-Assyrian palaces in Iraq. He heralded what modern scholars now consider “the rhetoric of stewardship,” making the case that the Iraqis were ill-equipped to preserve the ruins of the past and that they were neglectful of their own heritage. As a result, the British Museum to this day hosts the majority of the Assyrian palatial reliefs, a collection of their material culture, and a set of their protective, supernatural winged-bull sculptures known as lamassu.

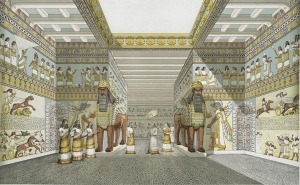

Compared to the realism of academic genre paintings or of classical Greek and Roman sculptures, the art of the Assyrians must have looked bizarre and out of place in Victorian London. Many Westerners knew about the region of Mesopotamia from Classical and Biblical texts that antagonized the Near Eastern kingdoms like the Assyrians and Babylonians, characterizing them as violent, sinful, and “other.” Layard even wrote himself that the artistic productions of the Assyrians were inferior to the beauty of Greek Antiquities. This view embodies the division between the Western and Eastern worlds and how it influenced the reception of the Assyrians. Comments like Layard’s failed to contextualize the achievements of the Assyrians, their ingenuity and inventiveness, but rather relegated them to victims of the fantasies of European society that had preconceived opinions of the sumptuous East. Later when Layard published his book about Nineveh he imagined the palatial interiors painted in Victorian pastels with architectural detailing like coiffured ceilings in an attempt to mold Assyrian society to the fashion of the Victorian age. The misrepresentation and misinformation about the Neo-Assyrians published at the time trickled down into the artistic circles of Western Europe. Shortly after the discovery of Nineveh, artists produced works that satisfied the Western fantasy of the distant and ancient Near East as a site of exoticism, brutality, and splendor.

Ford Madox Brown painted Dream of Sardanapalus in 1871. His painting portrays the king reclining in a chaise which would have been found in European homes, adding an element of familiarity to the scene for European audiences. Sardanapalus wears traditional Assyrian jewelry like the golden arm band with clasps in the shape of lions’ heads. He also has a prominent beard which relates to a common iconographical tribute in Assyrian sculpture which signaled a king’s virility. The scene is set in the room of the palace with relief sculpture present on the back wall. The reliefs depict battle motifs and a winged-hawk genie suggesting the artist studied the reliefs in the British Museum and took elements from them to create the relief sculpture present in the composition. A lamassu likewise frames the entrance into the room.

Presumably the painting refers to the death of the last Assyrian king. An archer stands in the background of the composition, his arms outstretched as he pulls back on the bow to shoot the arrow. The figure looks identical to those found in carved Neo-Assyrian reliefs. Brown’s painting displays a study in the culture and artistic production of the Neo-Assyrians that was readily available to him as an artist working in England after the discoveries of Layard. While the painting shows evidence of Brown’s observation of Assyrian visual culture, it also shows a conflation of Assyrian compositions and forms that place the scene in an imagined space, suggesting that the English still had much to discover in their understandings of the ancient Near East.

In the early 1900s, Austrian painter Gustav Klimt departed from the academic style of painting exhibited by the Romantics in the mid to late 1800s, but the mythology and artisanship of the Assyrians remained fresh in his mind. Well-known for his painting The Kiss (which also incorporates ancient Egyptian and Assyrian motifs in a composition reminiscent of Byzantine and Eastern Christian works), in 1901, Klimt painted Judith and the Head of Holofernes, a scene often depicted in academic paintings. Holofernes was believed to be an Assyrian general tasked with conquering western territories (he was actually sent by Nebuchadnezzar who was a Babylonian king so Holofernes may have been Babylonian; often Assyria and Babylon were conflated in the European imagination). Judith seduced Holofernes and beheaded him in order to save her people. In the work, Judith presents herself to the viewer holding the head of Holofernes found in the lower right hand corner of the composition. She

bares her chest, her head is slightly tipped back, her lips parted, and she caresses the head of her enemy. In academic paintings Judith is depicted as muscular and heroic, whereas Klimt endows his soft female figure with sexuality, capturing the sensation of Judith’s sexual sacrifice. While the painting recalls a story about an Assyrian figure, the association between the work and the past is not limited to the mythology of the event.

Judith is wrapped in a textile that recalls Neo-Assyrian motifs, and likewise wears a necklace similar to those uncovered in palatial tombs. The sheer fabric is adorned with circular patterning and while the detailing is unclear, potentially due to wear on the surface of the work, the circles appear to have rosettes in the center. The Neo-Assyrians used rosettes as a motif in jewelry and in sacred imagery as they referred to Ishtar, the goddess of love, war, fertility and sexuality. The inclusion of a symbol that refers to Ishtar resonates with the story of Judith in the context of Klimt’s work as a sexual woman who had recently committed an act of violence and brutality in the context of impending conquest.

The background mimics those commonly found in palatial reliefs from the palaces of Nimrud and Nineveh. Judith’s body rests against a patterned landscape comprised of layered oval-like forms with trees. In Neo-Assyrian compositions, the oval-like background signaled the setting of the scene in a rocky, mountainous terrain. The patterned background, including the depiction of trees, features prominently in the palatial relief composition of the Battle of Lachish from about 701 BC which details the Assyrian conquest of the Jewish fortified town. While the overall mission into Judah was largely unsuccessful for the Assyrians, Lachish was the site of a major victory. It is unclear whether Klimt was aware of the history of Lachish, or was conscious of the use of landscape patterning as a way to denote setting in Neo-Assyrian reliefs, but given that Judith’s confrontation with Holofernes was set in Bethulia, believed to be Jerusalem, the background may refer to the setting of the event in Judah.

Klimt’s use of symbols and motifs commonly found in Neo-Assyrian reliefs sparks associations with the history and mythology of the Ancient Near East to accentuate the story-line of Judith and Holofernes in his composition. However, the cooptation of Neo-Assyrian symbols also serves to remind the viewer of the position of Holofernes as an Assyrian general tasked with conquering the territory of Judah, feeding into the conception of Assyrians as violent but also sensual since he allows himself to be tempted by Judith. In this interpretation, Judith transforms into a champion for the West and an allegory for Western fantasies that had corrupted understandings of the “other.” While Klimt cleverly displays his understanding of the ancient civilizations through his use of their motifs in contrast to the sketches of Layard and the works of Brown and his colleagues, Klimt’s work still feeds into the notion of alterity and Orientalism. I find Klimt’s work intriguing because of the knowledge of Assyrian mythology and compositional technique that he exhibits, but his work still acts as an example of appropriation.

This brings me to a question that I have been wrestling with as a scholar of the Ancient Near East and a major in Middle Eastern Studies. Even if we strive to understand the region, its past, and its societies, as outsiders like Klimt, will our artistic and scholarly productions always be interpreted within the framework of Orientalism and the “other?” With the guilt of colonialism still influencing society, will we always be guilty of cultural appropriation?

Just wish to say your article is as astonishing. The clearness to your submit

is just cool and i can assume you are knowledgeable on this subject.

Fine together with your permission let me to grab your RSS

feed to stay updated with drawing close post. Thank you a million and

please carry on the enjoyable work.

LikeLike